Around the world, countries are spending more on their militaries, a trend that is already evident in the Western Balkans. In 2018, global military expenditure rose to 1.7 trillion US dollars, its highest level since the end of the Cold War. At a NATO summit in July, United States President Donald Trump insisted that the alliance should double its military spending target, from two per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) to four per cent. The European Union will spend more than five billion euros annually on funding defense research and arms acquisition through its new European Defence Fund.

These developments raise concerns about a military buildup in the region, either through hybrid warfare or new deployments and bases.

A quarter-century after countries in the Balkans reduced their military capabilities, many are beginning to reverse course. The trend is fueled by a media frenzy and political parties spewing ethnic hate-speech and pushing nationalist agendas.

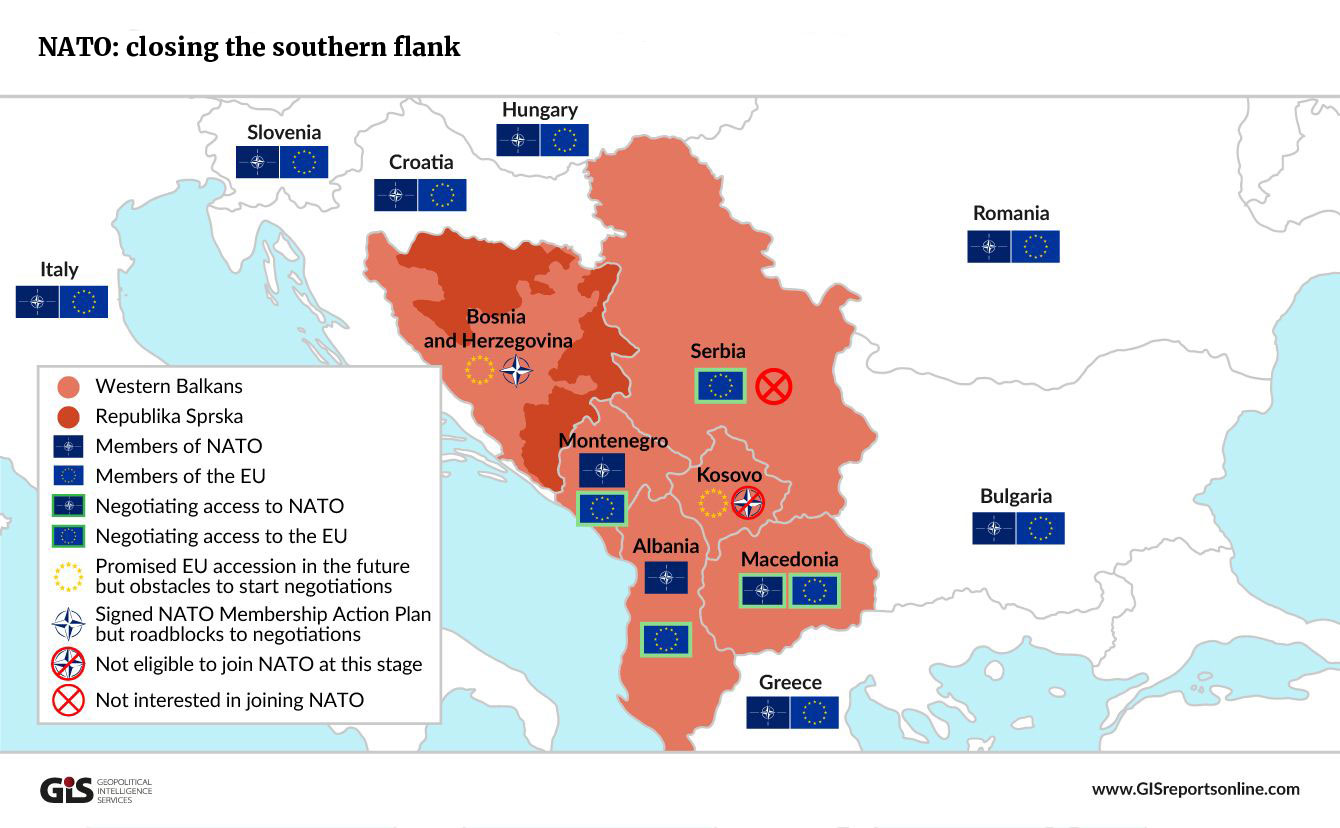

Unresolved disputes in the Balkans will offer justification for governments to strengthen their armies and keep democratic institutions weak. Global military powerhouses are already getting involved: Serbia and Republika Srpska (an autonomous, majority-Serb region in Bosnia and Herzegovina) will receive Russian weapons and even bases. NATO also plans to build bases in the region.

NATO vs. Russia

For now, most NATO aspirants from the Western Balkans do not meet the alliance’s two per cent of GDP defense spending goal. Macedonia last hit that target in 2007, when it spent 2.15 per cent of its GDP on defence. In 2018, the figure fell to one per cent. This resulted from a planned reduction in the country’s active military personnel, from about 8,200 to about 6,800.

In 2017, Serbia spent 731 million US dollars on its military, the most in the region, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Albania spent 162 million US dollars, Macedonia 112 million US dollars and Montenegro 74 million US dollars.

Serbia remains the Western Balkans’ strongest military power, with Albania a distant second. Kosovo will transform its “Security Forces” into a standing army this year. Bosnia and Herzegovina, teetering on the edge of becoming a failed state, wants to become a NATO member. However, Republika Srpska – which can veto such moves at a federal level – will block any such initiative. It is worth noting that three weeks ahead of general elections last year, Republika Srpska got a visit from Russia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergei Lavrov.

Even Serbs outside Serbia are blocking other countries in the region from joining NATO, while Serbia’s army still relies on Russia support. Only about three per cent of Serbian citizens support their country joining NATO, while in Albania the figure is about 90 per cent. Most Macedonians also support NATO membership, despite the flood of Russian anti-NATO propaganda ahead of last September’s referendum on joining. Several high-placed EU and US officials, including German Chancellor Merkel and US Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, visited the country to counteract the Kremlin’s campaign. Last year, the US Congress approved eight million US dollars to help Macedonia fight Russian propaganda.

It is likely that hybrid war and military competition will divide the region into two security zones: one under the Russian umbrella (Serbia and Republika Srpska) and the second with the Euro-Atlantic aspirations (Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia and Montenegro).

Land-swap proposal

The military map of the Balkans is simple: Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are not members of NATO, but adjoin countries that are members of the alliance. Russia is present in the region, through its Russian-Serbian Humanitarian Centre in Nis. The centre has not received diplomatic status despite a strong push from Moscow, since many Western governments accuse it of engaging in intelligence activities. This base is close to Serbia’s borders with two NATO members – Bulgaria and Romania – as well as two NATO aspirants – Macedonia and Kosovo. Russia now also plans to establish a regional center for servicing its military helicopters, and recently announced it would deploy troops to Serbia.

NATO’s Kosovo Force (KFOR) has had a base in Kosovo since 1999 and will soon begin building an air base in Kucova, Albania. This renewed military buildup will create serious tension in the region.

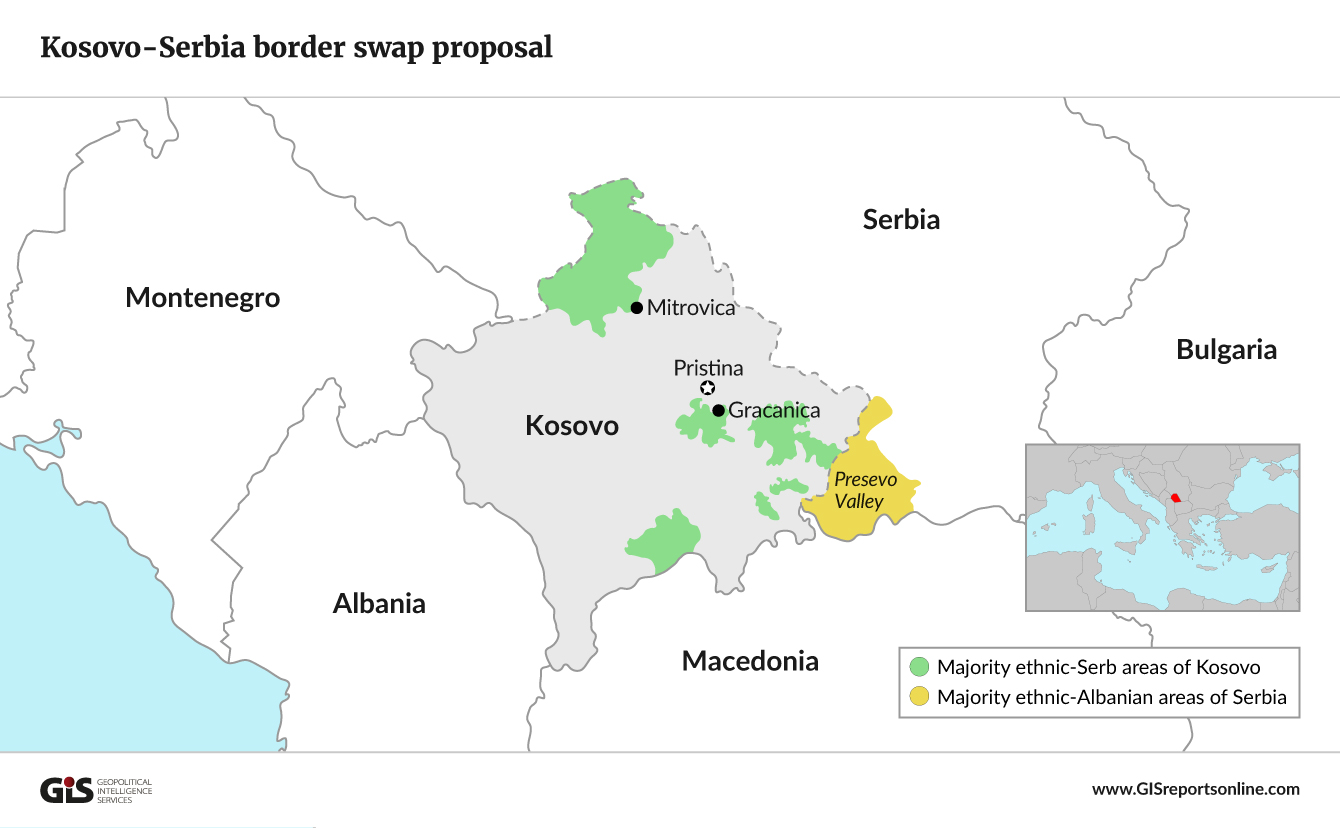

All this is occurring while a Pandora’s box of border issues has again been opened. A proposal for a border adjustment/land swap between Serbia and Kosovo has divided the main players in the region into four blocs: Germany and the United Kingdom (German Chancellor Angela Merkel and British Prime Minister Theresa May explicitly oppose the idea); the European Commission, (EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Federica Mogherini and EU Enlargement Commissioner Johannes Hahn are implicitly for it); the US (National Security Advisor John Bolton is watching closely but has made no decision either way); and Russia (Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Maria Zakharova has said the Kremlin remains neutral and would “accept any agreement that is good for Serbia”).

Military and border issues are very much linked in the Balkans, as politicians in the region frequently call for sending soldiers to protect frontiers. Unsurprisingly, the leaders that support the proposal both have extensive background in military conflict: Kosovo President Hashim Thaci was a leader in the Kosovo Liberation Army, while Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic was minister of information under former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, on whose watch the Balkans wars of the 1990s began.

The debate over the land swap between Serbia and Kosovo has cropped up just as Russia and NATO are reinforcing their military stances in the region. This is because regional peace will depend on how the two biggest ethnic groups there – the Albanians and the Serbs, each numbering about seven to eight million people – resolve their disputes.

For more than a century, peace in the Balkans has been waiting on a sustainable, lasting peace between these two peoples. Secret talks between leaders are unlikely to achieve this goal, however. World War I, which started in the Balkans, began as a result of secret alliances. The main question is whether redrawing the borders will lead to peace or more war. Croatian Minister of Foreign and European Affairs Marija Pejcinovic Buric has openly questioned what kind of precedent such a land swap would set.

The answer is that it would probably have a domino effect on other parts of the region, such as Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Only a real reconciliation between Kosovo Albanians and Serbs – with mutual recognition of statehood – can halt the new military build-up. That seems unlikely in the short term, given recent statements by Serbian Minister of Foreign Affairs Ivica Dacic, who has said that Serbia will never recognise Kosovo as an independent state.

In November, after heavy lobbying from Serbia to deny Kosovo entry into the international police organisation Interpol, the government in Pristina slapped a tariff of 100 per cent on imports from Serbia. Soon after, Albania and Kosovo signed a customs unification agreement. Belgrade warned that Albania and Kosovo were moving toward unification. Serbian Defense Minister Aleksandar Vulin said his country’s army was “prepared” to invade Kosovo to protect Serbs living there.

In December, Kosovo’s parliament voted to create a 5,000-strong standing army, again ratcheting up tensions. Serbian Prime Minister Ana Brnabic suggested her country could intervene militarily, and President Vucic traveled to the Serbia-Kosovo border to inspect the troops there. Earlier in the month, Serbian media reported that the US had sent a shipment of weapons to Kosovo’s security forces. Albanian media report that Kosovo’s budget for its army next year will be 98 million euros. Pristina has insisted that its army will be used to contribute to international efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq, and will not be used against the Serbs in its own territory or against Serbia itself.

Strategic focus

The Balkans will probably be a strategic focal point of US security strategy. At the July 2018 summit, NATO concentrated on shoring up security from the Baltic Sea to the Balkans, especially to counter Russia. In addition to the new NATO air base in Albania, it is likely that the US will make the KFOR base a permanent one, as well as station the current 3,000 troops in Poland permanently in that country, as requested by Warsaw. Such moves are in line with the Three Seas Initiative to create a zone of stability in between the Baltic, Black and Adriatic seas.

During the Cold War, southeastern Europe was strategically balanced through a 2+2+2 formula: two NATO members (Turkey and Greece), two Warsaw Pact states (Bulgaria and Romania) and two states not within any military bloc (Yugoslavia and Albania). Today, Bulgaria, Romania, Montenegro and Albania have all joined NATO. Russia is returning to the region via its allies Serbia and Republika Srpska. However, Macedonia will likely become the 30th member of NATO this year, while Kosovo also hopes to join. It hosts Camp Bondsteel – the main US Army base under KFOR command – one of the largest American military bases in Europe.

NATO air base

For a long time, the only foreign military base in the Balkans was a Soviet navy base on Sazan Island in Albania. Then Albania left the Warsaw Pact and remained neutral for four decades until becoming a full NATO member in 2009. Now, it will soon host the first NATO air base in the region, securing the alliance an important strategic site, just an hour’s flight from Syria.

In August 2018, NATO announced it would invest some 51 million euros in the air base in Kucova – and that is just the first phase. The facility will provide fuel, logistics and policing support, as well as training for the transatlantic alliance. The site once served as a base for the Albanian Air Force but has not been used in years and had fallen into disrepair.

It seems that NATO decided to establish its first air base in the Balkans as a consequence of what it considered a new aggressive military stance by Russia, culminating in the annexation of Crimea in March 2014. In April 2018, Albanian Defense Minister Olta Xhacka and U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis finalized the air base deal during talks in Washington.

The Kremlin’s reaction was swift. Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev called the basing decision a “provocation” and said that Moscow would not simply “stand by and watch” while it was built. Russian news services even warned that NATO was encroaching on Russia’s “border.”

In September, Russia held the Vostok 2018 (East 2018) military exercises. Some 297,000 soldiers were reported to have been involved, making it the largest military drill since the height of the Cold War. Serbia, a key Russian ally in the region, participated in those exercises. In August, Serbia’s air force took delivery of two Russian MiG-29 fighter jets. Belgrade and Moscow are also due to sign several arms deals, including for tanks and rocket systems, when Russian President Vladimir Putin visits Serbia on January 17.

It has been reported that Serbia will also purchase the Russian-made S-300 air defense system and six more MiG-29 jets from Belarus, along with several unmanned air vehicles for military purposes from China. Serbia is also supporting the buildup of Republika Srpska’s security forces.

Moreover, during his visit to Kosovo in September, President Vucic made a speech in which he indirectly praised Slobodan Milosevic. With disciples of Milosevic like Mr Vucic and Mr Dacic in power in Belgrade, any new demilitarisation of the Balkans seems a long way off.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario would see both Russia and NATO increase their military presences in the region, including new bases. Despite the failed referendum in Macedonia, it seems likely that the country will become a NATO member, perhaps by the end of 2019. When that happens, the alliance’s southern flank will be closed, and two pan-European transport corridors (VIII from Durres, Albania to Varna, Bulgaria and X from Salzburg, Austria to Thessaloniki, Greece) will come entirely under NATO protection. Greece’s warming relationship with the US is crucial in this context.

Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina will be completely surrounded by NATO members, save for their mutual border. It is likely that Serbia initiated the talks on a territorial exchange with Kosovo to disrupt this process by creating a new conflict zone in the Balkans.

Talks on the land swap have been put on hold due to the strong opposition of Chancellor Merkel and Prime Minister May. The two sides are unlikely to reach an agreement before mid-2019, when the current European Commission’s mandate ends. The EC has gone back and forth over whether to support the deal, with Commissioners Mogherini and Hahn backing it in a last-ditch effort to claim a “success” in the dispute before their terms are up.

It is also likely that the military buildup in the region is part of a broader tug-of-war for strategic advantage around the Mediterranean Sea. In this context, it is important to note Russia’s newly gained influence and its military bases in Syria; especially after President Trump’s recent decision to withdraw US troops stationed there. Moscow can stir up conflict there, sending more refugees to Europe and destabilising European governments. With Macedonia in the alliance, NATO will have closed its flank to the Middle East. The alliance’s influence – and likely growing presence – in the region will stabilise southeastern Europe in the coming years.

—

This article was originally posted on GIS Reports Online, founded by HSH Prince Michael of Liechtenstein to provide unbiased, scenario-based geopolitical forecasts to inform their strategic decision-making. It is reproduced here with permission. The views expressed in this opinion editorial are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Emerging Europe’s editorial policy.

Published by: emerging-europe.com